Table of Contents

Introduction

Maybe you have been shooting past 1000 yards since before 6.5 Creedmoor was around. Maybe you are just getting into long-range shooting and you don’t know what the difference is between G1 and G7 ballistic coefficients. Maybe you just have more money than sense and buying more golf clubs just isn’t cutting it for you anymore. No matter what your situation is, you have found yourself overwhelmed with choices for a new scope for your rifle and despite reading everything you can online, watching countless hours of YouTube videos, and talking to your buddies and the local gun shop, you still don’t know where to start. In this article, we will discuss exactly how you can find the right scope for your needs.

Decision Criteria

Picking the right scope may not sound easy at first. Most long-range shooters will have their favorite brands they swear by, and scope choice can be extremely personal and subjective. Your application, preferences, and requirements may differ from those of other shooters. It can be helpful to pick 2 or 3 criteria that you absolutely need, and then 2 or 3 that you would prefer but are not strictly necessary. Doing so will narrow down the scope of your options (no pun intended) significantly.

Let’s break down the important factors we need to consider when choosing a long-range scope:

Cost

Your budget for a scope is one of the best places to start. You might find the perfect scope for your needs with best-in-class glass quality by Schmidt & Bender or Nightforce, but if the price point is 5 times higher than you are willing to spend, one of these scopes simply will not work for you. Once we have a price range or budget, we can find appropriate scopes with a reasonable price.

One rule of thumb in the long-range shooting world is: Spend as much on your glass as you did on your rifle. You do not want your rifle to be limited by the optic you choose for it. With optics, like with rifles and many other things in life, you get what you pay for. That being said, we also see diminishing returns in long-range optics: a $2000 scope is not necessarily twice as good as a $1000 scope, and when we start talking about even higher-end optics, a $2000 price difference between scopes may only result in a very small improvement in optical quality or a slightly higher magnification.

Magnification

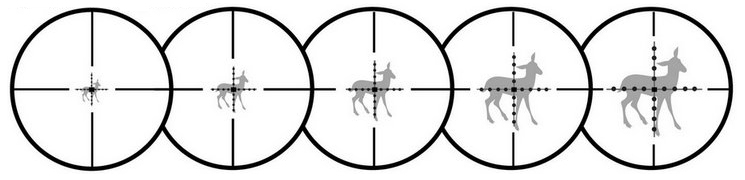

While the snipers of days gone by may have used fixed 10x scopes for shooting 1000 yards, optics have become increasingly more affordable and that kind of magnification simply will not cut it for most shooters today. While it is easy to fall into the trap of putting the most powerful scope you can find on your long-range rifle, magnification is not the end all be all for this type of shooting.

For most shooters, a 25x scope will work well to around 1000 yards and a bit beyond. For the guys shooting 2-mile competition, they are usually only using around 35x scopes at the high end. Skilled shooters using 16x scopes can easily get out to 1200 yards, and as mentioned above, 10x scopes used to be commonplace for these kinds of distances.

While having the right magnification for what you need is critical, glass quality and other features also play an important role. In many cases, spending your limited budget on a higher quality scope with slightly lower magnification may be a more sound choice than buying a budget scope with high magnification. Oftentimes, shooters using high-end glass find themselves not needing as much magnification because of the quality of the image produced by the scope, and can benefit from the advantage of having a larger field of view and more reticle to work with, assuming a first focal plane scope.

Focal position

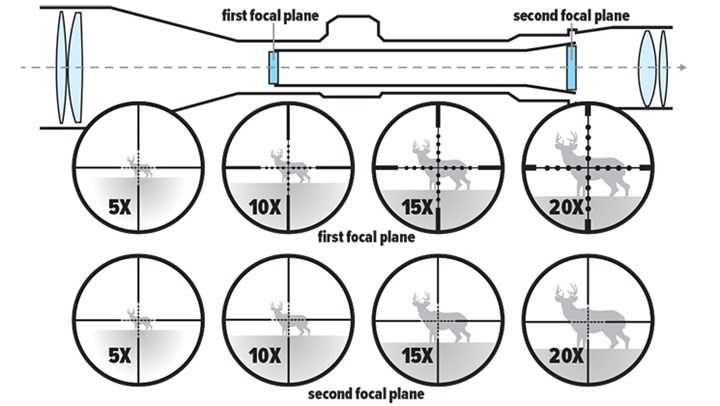

The choice between first and second focal plane optics is a major concern for both new and experienced shooters alike and is largely a personal preference. Many lifelong shooters still have not looked through a first focal plane optic. Traditionally, most scopes were second focal plane, but first focal scopes have become increasingly more affordable and now dominate the long-range shooting world.

With traditional second focal plane optics, the apparent reticle size always stays the same in relation to the shooter’s eye, regardless of magnification. As a result, the reticle size changes in relation to the target as magnification increases or decreases. On the other hand, the reticle in a first focal plane optic always stays the same size in relation to the target. As a result, the reticle size and the target size will appear to get smaller as the magnification decreases, or appear to get larger as the magnification increases.

The benefit of a first focal plane reticle is that the shooter can use the reticle for holding over (or for estimating the distance of a known size target) at any magnification. On a second focal plane scope, the reticle can only be effectively used for holding or for ranging at one given magnification (usually, but not always the highest magnification). This is a huge advantage for first focal plane optics, because the highest magnification is not always optimal for any given shooting situation. For example, if we imagine shooting a target on a two way range, using a lower magnification will allow for a wider field of view to see other potential targets or threats.

Depending how you will be using your scope however, a first focal plane reticle may not always be advantageous. If you will always be shooting at the highest magnification, you will never see the benefit of first focal. If you will be shooting a lot at the lower end of the magnification range, a second focal plane reticle will be easier to use because the reticle will be larger and more bold than with a second focal plane reticle. If you never use the reticle for holding over, and you always dial, again; there will be little benefit to a first focal plane reticle.

Reticle style

Like focal position, reticle style is also largely personal preference, probably moreso. A very busy, technical reticle can be extremely useful for ranging, holding over, or leading moving targets for some, but may be far too cluttered and obscure the target too much for many others. On the other hand, a very simple, fine reticle may be great for certain types of competition shooting, but difficult or impossible to use for ranging, holding over, or leading moving targets.

Using Nightforce as a case study, we can see the range of reticle styles available:

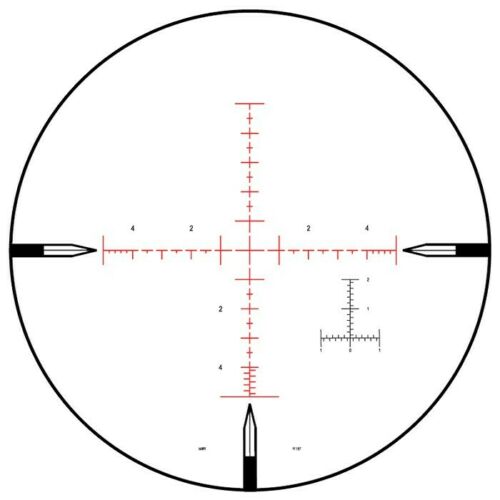

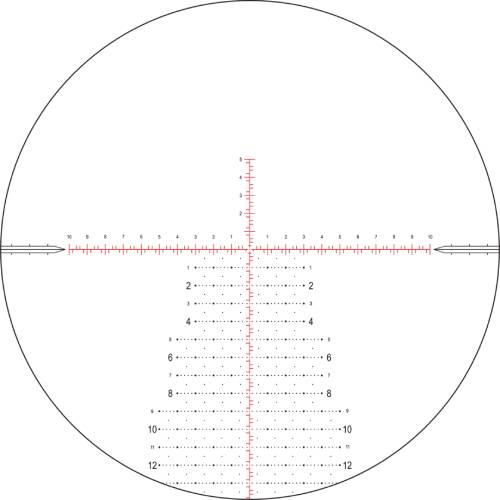

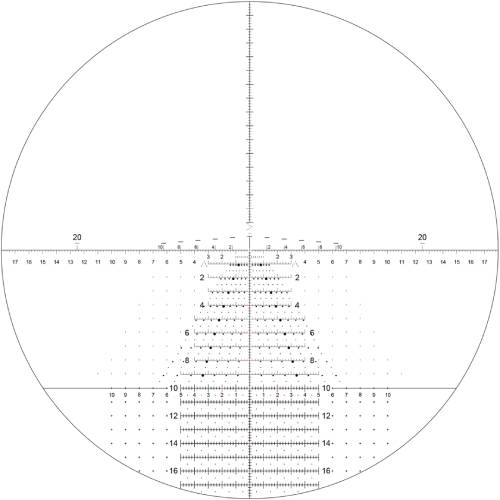

Mil-R : The Nightforce Mil-R reticle is fairly simple and uncluttered. The center of the reticle is open, but we have 0.5 mil hold points throughout, and 0.2 mil subtensions on the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock edges and a ranging tree offset down and to the right.

Mil-XT : The Mil-XT reticle is two steps more busy than the Mil-R reticle. The Mil-XT is based on the Mil-C reticle but features windage holdover points extending horizontally along the lower axis. The illuminated subtension likes are also much closer together than on the Mil-R. This type of reticle is often referred to as a Christmas tree style, although it would be a bit more accurate to call it a grid.

Tremor 3 : The Tremor 3 reticle is one of the busiest reticles on the market. It has some similarities to the Mil-XT, but there are dots and lines throughout the reticle. Each marking on the reticle has a specific purpose which can be used for long-range shooting, but the sheer number of the features can clutter the image and distract some shooters.

Choosing the right reticle is deeply personal, and if you have one favorite you would like to stick to, or a couple you would want to avoid, you can narrow down your options significantly.

Turrets

Turret style and features are critical for a long-range scope, as the turrets will be used quite often for most long-range shooting. Most long-range scopes should have an exposed elevation turret with a zero stop system of some kind. An exposed windage turret can be helpful for some shooters, as can a locking feature on the turret(s). Some scopes even have revolution indicators so you know where your elevation turret is relative to its total travel.

Exposed turrets are necessary for making quick adjustments for shooting further than your zero distance. While a first focal plane reticle can be used even quicker, being able to use both the turrets and reticle is a great skill and can be combined to shoot even further.

A zero stop will allow you to return back to your zero distance without a second thought. Assuming you have a 200-yard zero, you then need to adjust the scope some clicks to shoot out to say 500 yards. After you are done shooting at 500 yards, you can simply turn the turret until it stops at your zero point and know you are right back where you started for next time. This eliminates the need to have to count your clicks to get back down to your zero and removes any confusion if you have to make multiple turret rotations. Some scopes will allow you to dial down past your zero (sub-zero) so you can make closer range shots if needed. However, even if your scope does not have this feature, you can still set your zero stop just a bit below your zero setting.

A locking turret feature allows you to carry your rifle around without having to worry about your turret getting bumped or otherwise adjusted where you don’t want it to be. Some shooters do not shoot in multiple positions or otherwise carry their rifle around, or can find that a locking feature can be annoying to have to unlock every time the turret is adjusted. Some turret styles, like the Leupold M5C3 turret found on the Mark 5HD, will only lock at the zero setting. Others, like the S&B MTC LT, can be locked at any setting.

An exposed windage turret can be a handy feature in some cases. While most shooters prefer to dial elevation and hold for wind, some prefer the ease of adjustment for dialing windage on the fly. However, unless the windage turret has a locking feature, it can be one more vulnerability to bumps otherwise inadvertent adjustments.

Most long-range scopes will have multiple turns of elevation on the elevation turret: in some cases 5 or more turns. After the second or third turn, it can be easy to get lost in your turret travel, and you may find yourself wondering if you’ve made two turns or three, or 20 mils or 30 mils of adjustment, in an extreme example. In this situation, a revolution indicator is very useful. With the Leupold M5C3 turret, the revolution indicator is the same button used for the turret lock. With the S&B MTC turret, a revolution indicator pops up from the top of the elevation turret. These types of indicators are easy to use, even in the dark.

Illumination

Most long-range scope manufacturers offer reticle illumination, some as a standard feature and some as an option. Reticle illumination can be very helpful when shooting in sub-optimal lighting conditions (early morning, late night, etc.) and can sometimes even be useful when shooting a dark target; to get a little contrast between the reticle and your target. Although it is outside of the scope of this article, reticle illumination is also very helpful if you are using the scope with a clip-on night vision or thermal device.

Some reticles, like the H59 and Tremor 3 reticles from Horus, have very small illumination points that are not very bright. This is important to consider if you are only using the scope during broad daylight hours, as there may be no reason to pay extra for illumination on a scope with these reticles if you have an option. With the Leupold Mark 5HD scopes, for example, illumination is an extra $200-$300, so carefully consider whether illumination is important for your application.

MOA vs MRAD

While your reticle subtension and turret adjustment measurement should match, whether you choose MOA or MRAD is simply a personal choice and should have very little bearing on your scope decision. Both units of measurement accomplish the same thing. It would be difficult to argue that measuring your weight in pounds or kilograms is superior, or your height in inches or centimeters is better. Of course, you are likely much more comfortable and familiar with one set of measurements over the other.

All that said, the typical ¼ MOA adjustment found in MOA scopes is a very slightly finer adjustment than the 0.1 MRAD adjustment found in MRAD scopes. There tend to be more MRAD based reticles than MOA-based reticles from most major scope manufacturers, and some reticles are only offered in MRAD, like the Horus reticles.

If all of your shooting buddies use MOA, it may be easier for you to go MOA. If your instructor only uses MRAD, then it may be easier for you to go MRAD. However, a good shooter will be proficient with both measurements and be able to easily convert between them.

Great Picks

Around $1000

Around $2000

Over $2000

FAQ

General rule of thumb is to spend at least as much on your scope as you did on your rifle. You get what you pay for.

Around $1000 will get you an excellent long range scope.

Not necessarily. As with many things in life, we see diminishing returns on long range optics. For many shooters, squeezing out a bit more performance can be worth quite a lot.

25x on the top end will get most shooters to 1000 yards and beyond.

No. Sometimes it is important for a shooter to see the target’s surroundings for hunting, tactical shooting, or even adjusting for missed shots on the fly.

Most shooters prefer first focal. If you are using the reticle for holding over AND not using the highest magnification regularly, then a first focal scope is a good idea. If you are regularly using the scope at low magnification, or you always use the turrets to compensate for windage/elevation, or you always use the highest magnification, then a second focal scope should work fine.

If you have to ask, go with something fairly simple.

Look for exposed elevation, firm tactile clicks, and a zero stop. Exposed windage, locking turrets, and revolution indicators are nice to have.

For most shooters, illumination is not a necessity, but it can be helpful.

It doesn’t make much of a difference; use what you are most comfortable with. If you are just getting started, MRAD is more common in the professional and competition shooting world.